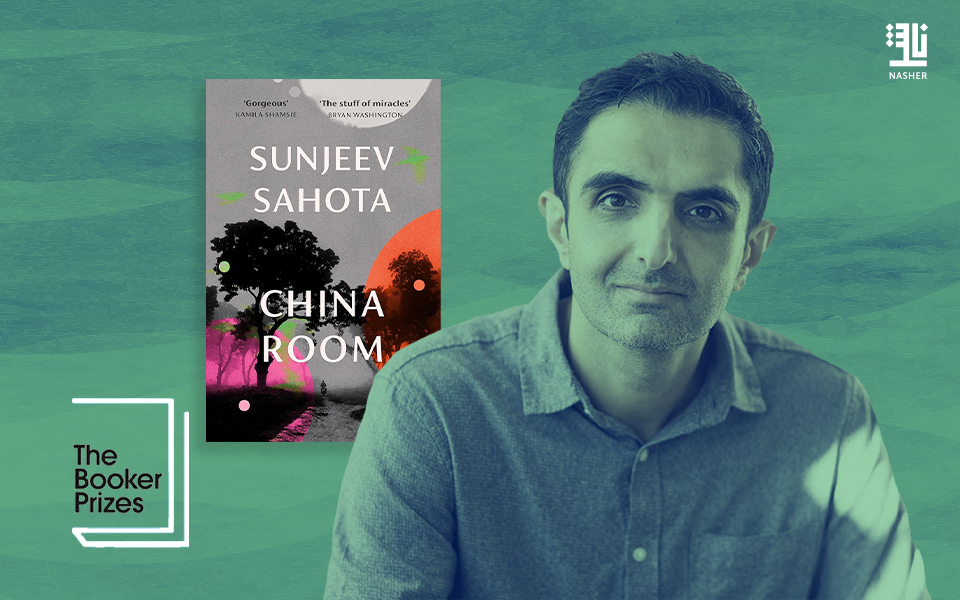

China Room is a tale of injustice that narrates the story of an alienated youth who travels to remote rural India, where his great-grandmother lived in 1929, at 18, he is in the throes of heroin addiction. His account of a summer spent in rural Punjab is interspersed with the more substantial third-person story of a young woman – his great-grandmother.

The narrator takes up an opportunity to combat his addiction by visiting an uncle in Punjab before he starts at a London university; he goes armed only with whisky and a selection of books “all by or about people who had already taken their leave”. His reading list – Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, Natalia Ginzburg’s The Little Virtues, a biography of Leonora Carrington, poetry by Les Murray – is a summary of what troubles and interests him: addiction, family, memory, surrealism, belonging and unbelonging.

Later in the novel he realises that he hopes “reading about life might be a way to overcome it”. But it is the story of Mehar, a 16-year-old bride who finds herself living in the “china room” – a cramped, hitherto seldom used building on a farm, its nickname derived from the willow-pattern plates that adorn it, which once formed part of a dowry – that looms largest in the novel. Mehar shares the room with Harbans and Gurleen, whom she has only recently met; the three of them have been married, in a single day, to three brothers. Now, they spend their days doing chores and waiting for the matriarch, Mai, to tap one of them on the shoulder, thereby summoning her to a bedroom to meet her husband and, it is hoped, become pregnant with a son. Yet Mehar enjoys the affection she shares with her new “sisters” and notes the simple beauty of her rural surroundings — how the moon “on the ground glimmers brokenly like a shoal of ghostly fish.” But she also recognises the gender inequality that exists “she’ll wonder if that is the essence of being a man in the world, not simply desiring a thing, but being able to voice that desire out loud”.

The narrative’s most important driver is that, while each of the brothers knows which wife is “theirs”, the veiled young women do not. Sex takes place in darkness, with only the briefest of verbal exchanges; the rest of the time, segregation between husbands and wives is near total. Until it isn’t. We know that Mai’s own marriage, and the subsequent death of her husband, influences her often callous single-mindedness, but details are scant.

Though married to the oldest brother, Mehar falls in love with one of the younger ones, originally matched to her but switched at the last minute. This love proves to be the downfall of both, despite the notion echoed by the character ‘You know what the best thing is about falling out of love? It sets you free. Because when you’re in love it is everything, it is imprisoning, it is all there is, and you’d do anything, anything, to keep that love. But when it withers you can suddenly see the rest of the world again, everything else floods back into the places that love had monopolised.’ In China Room, love is a form of imprisonment.

We know too that the pressure of political and economic events, many centred around restless, dangerous independence movements, contribute to the claustrophobia and tension on the farm; that questions of caste, religion and sexuality are always present in the background. But although these realities inflect the characters’ responses and behaviours, they are never allowed to stifle what is essentially a novel of interior life and sensation.. Here, events are glanced at, elaborated in fragments and elliptically, the reader left to draw a line leading from the earlier story to the life that the narrator has lived in the north of England, complete with its painful incidents of exclusion, racism both covert and explicit.

Both storylines converge in themes of escape and incarceration, whether literal or social and psychological. The narrator, living alone on the abandoned farm, having been shunned by his aunt and uncle, plays out an almost parodic tale of regeneration and reconnection that echoes Mehar’s less successful attempts at self-determination; their familial link hovers over the entire story, reminding us of the ghost-trauma carried from generation to generation.

China Room by Sunjeev Sahota is published by Random House, on 6th of May 2021 and was longlisted for the Booker Prize 2021. Although China Room was thoroughly an enjoyable read, the constant shift from the present to the past was somewhat distracting and disrupted the flow of the story, we have given it a rating of 7/10.