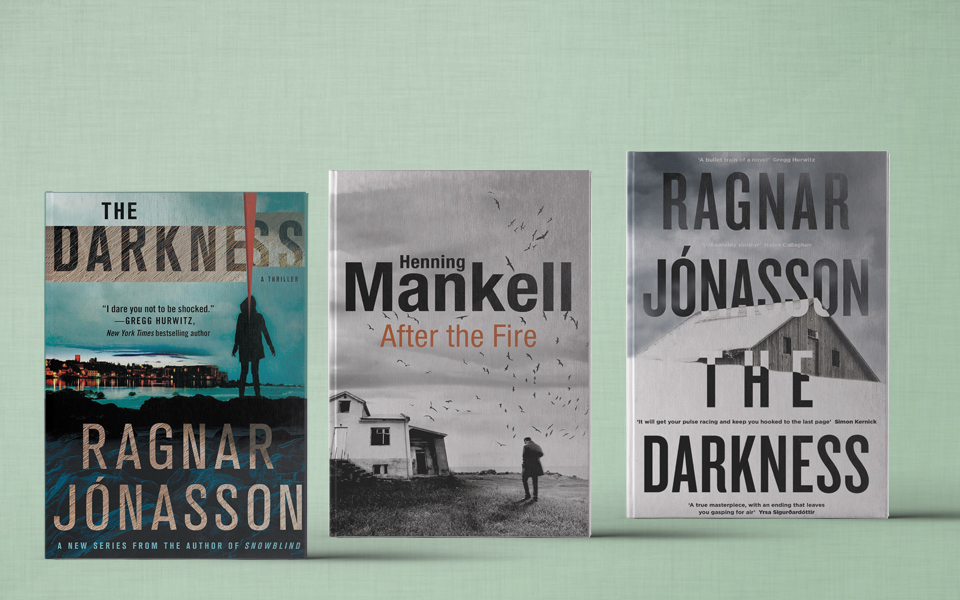

Scandinavia is a bleak, ungodly, extraordinarily violent place to live, Over the past decade Scandinavia has become the world’s leading producer of crime novels. The two Swedes who did more than anyone else to establish Nordic noir-Stieg Larsson and Henning Mankell have both left the scene of crime. Larsson died of a heart attack in 2004 before his three books about a girl with a dragon tattoo became a global sensation. Mr. Mankell consigned his hero, Kurt Wallander, to Alzheimer’s after a dozen bestsellers. But their books continue to be bought in their millions: Dragon Tattoo has sold more than 50 million, and the Wallander books collectively even more.

The region has a long tradition of crime writing. Per Wahloo and Maj Sjowall, a Swedish husband-and-wife team, earned a dedicated following among aficionados with their police novels in the 1960s and 1970s. They also established two of Nordic noir’s most appealing memes. Martin Beck is an illness-prone depressive who gets to the truth by dint of relentless plodding.

A group of new writers, such as Jo Nesbo in Norway and Camilla Lackberg in Sweden, are determined to keep the flame burning. And the crime wave is spreading beyond adult fiction and the written word. Sweden’s Martin Widmark writes detective stories for children. Swedish and British television producers compete to make the best version of Wallander. The Killing established a new standard for televised crime drama.

There are a few reasons Scandinavian writers have taken to the genre. The crime novel, and particularly the British crime novel, has been enormously popular in Scandinavia for decades. And the famous Nordic pragmatism is well-suited to the intricate mechanics of crime investigation plots. But the best explanation is the most mundane: Crime novels sell. Most of the Scandinavian crime novelists began their careers in other genres. Mankell, for instance, wrote seven well-received but unlucrative novels, and more than a dozen plays, before turning to a life of crime; Karin Fossum was a prize-winning poet; Maj Sjöwall was an editor and translator. Before the current explosion of crime novels, the only contemporary Scandinavian novelist to enjoy major international success was Peter Hoeg. Hoeg may be a “literary” novelist, but his breakout Smilla’s Sense of Snow is about the investigation of a suspected homicide. The lesson is clear: If you want your novel to be read abroad, particularly in the English-speaking world, you’d better include a murder. Even if you’ve never heard of a murder actually being committed in your country.

Stieg Larsson, like many of the other successful Scandinavian crime novelists, began in the straight world, editing an anti-racism magazine and several science fiction fanzines and writing political journalism. In 2004, shortly before dying of a heart attack, Larsson completed the first three novels of a planned decology. The second volume, The Girl Who Played with Fire, will be out in the States this July and will likely confirm Larsson’s position as the most successful crime novelist in the world. His novels mark the apotheosis of the genre—they are not only the best-selling, but they are also the most frenzied and exhaustive examples of the form.

To an even greater extent than Mankell, Larsson is adept at heightening the contrast between his setting, contemporary Stockholm, and the tawdriness of the crimes that drive his plots. Larsson’s Stockholm manages to be both cosmopolitan and charmingly quaint. It’s not unlike the Ikea approach modish design with a side of Swedish meatballs. (Larsson, in fact, sets an entire scene at the store, when a character moves into a new apartment, she goes on a shopping spree, buying 12 items, including an “Ivar combination storage unit” a “Pax Nexus three-door wardrobe” and a “Lillehammer bed”

Today’s crime writers continue to profit from these conventions. Larsson’s Sweden, for example, is a crypto-fascist state run by a conspiracy of psychopathic businessmen and secret-service agents. But today’s Nordic crime writers have two advantages over their predecessors. The first is that their hitherto homogenous culture is becoming more variegated and their peaceful society has suffered inexplicable bouts of violence (such as the assassination in 1986 of Sweden’s prime minister, Olof Palme, and in 2003 of its foreign minister, Anna Lindh, and Anders Breivik’s murderous rampage in Norway in 2011).

Nordic noir is in part an extended meditation on the tension between the old Scandinavia, with its low crime rate and monochrome culture, and the new one, with all its threats and possibilities. Mr. Mankell is obsessed by the disruption of small-town life by global forces such as immigration and foreign criminal gangs. Each series of The Killing- focuses as much on the fears-particularly of immigrant minorities-that the killing exposes as it does on the crime itself. The second advantage is something that Wahloo and Sjowall would have found repulsive: a huge industry complete with support systems and the promise of big prizes.

Ms. Lackberg began her career in an all-female crime-writing class. Mr. Mankell wrote unremunerative novels and plays before turning to a life of crime. Thanks in part to Larsson, crime fiction is one of the region’s biggest exports: a brand that comes with a guarantee of quality and a distribution system that stretches from Stockholm to Hollywood.