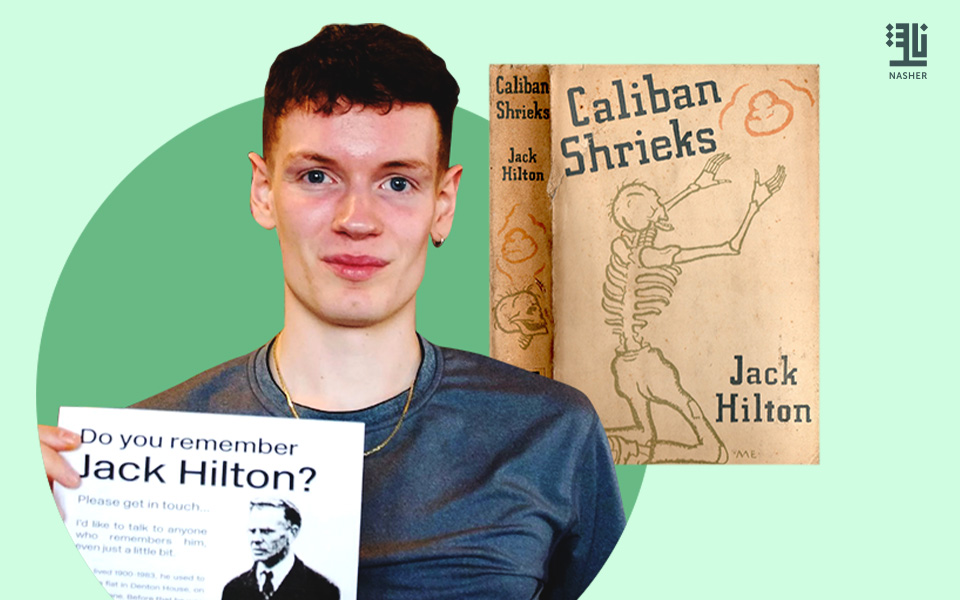

A 1930s novel that was acclaimed by George Orwell and WH Auden before being forgotten for decades is to be republished after a Manchester bartender rediscovered it and solved a mystery about the author’s last wishes. The name of author Jack Hilton was lost to history before a 28-year-old bartender set out to uncover his legacy. Now, following a campaign to get the book back into print, it has been signed by Vintage (Penguin), the UK’s largest publishing house.

Jack Chadwick chanced upon an old copy of Jack Hilton’s semi-autobiographical Caliban Shrieks in 2021.

Academics had previously failed to find who inherited the rights to the book after Hilton died in 1983. But Chadwick succeeded by appealing for information in pubs near the writer’s last home.

He put up posters asking “Do you remember Jack Hilton?”, which eventually led him to track down the widow of a friend, who was unaware she had inherited the author’s estate.

Chadwick then launched a campaign to get the book back into print, and it has now been signed by Vintage, an imprint of Penguin, the UK’s largest publishing house. Hilton was the favourite author of illustrious names like W. H. Auden and George Orwell. But unlike these famous names, Hiltons was lost to history.

Through a painstaking investigation, Chadwick tracked down Hassalls home address, as she represented his last hope of unearthing the truth. Chadwicks journey began last summer in the Working Class Movement Library, located in the streets of Salford in the north of England.

I came across this weird, crumbling, ancient book with this strange cover of a skeleton kneeling with its arms outstretched, says Chadwick.

Fascinated by the out-of-place nature of the book in a library which is predominantly filled with information on the labour movement and trade union meeting minutes, Chadwick opened the book.

Opening with quotes from Shakespeares The Tempest’, the novel was Caliban Shrieks, which details the early life of Jack Hilton, from a childhood in the industrial heartlands of Northern England to his participation in the First World War. Through Hilton, the reader experiences a first-person interrogation of a childhood characterised by infant-mortality and child-labour.

Hilton and his siblings all went to work in the Mills Greater Manchester aged 11, and only one of his sisters lived past 30. The book goes on to describe his peer-pressured enlistment in WWI, the Battle of the Somme, and returning to the UK to process his trauma as a wandering vagrant. After making enquiries to the now-retired librarian, Chadwick discovered that the author was a mysterious figure. Active between 1934 and 1950 before disappearing into obscurity, nobody seemed to know much about him.

That the book was by an author that no one had heard of just grabbed me, says Chadwick.

Orwell even asked to come and stay with Hilton in Rochdale to write his own account of English working-class life. Hilton didn’t have room, but suggested a friend in Wigan instead. That led Orwell to write his landmark The Road To Wigan Pier, which was published two years after Caliban Shrieks.

Chadwick said Hilton was “a writer of great talent who came from nowhere to blow wide open the parameters of literary modernism”.

Hilton went on to write several more books, but went out of fashion and out of print after World War Two, when one countess at a leading publishing house was said to have told him that “the proletarian novel is dead”.

Seven decades later, a tattered copy of the book caught Chadwick’s eye at Salford’s Working Class Movement Library. He was soon engrossed by the book and intrigued by the fact it and its author seemed to have been largely forgotten.

The few scholars who were aware of Hilton had unsuccessfully tried to track down the owners of the rights to his work, which would be required to reprint his books.

Hilton, who did not have any children, was thought to have died in Wiltshire. But Chadwick tracked down his death certificate and discovered he had actually moved to, and died in, Oldham.

Chadwick put up the appeal posters in pubs near Hilton’s last address. In one, before he had finished his pint, a woman approached him and gave him the names of the writer’s two best friends.

The friends too had passed away, but Chadwick tracked down the widow of one and put a letter through her door.

Through another stroke of luck, during further research, he found a document that said Hilton had left his copyrights, along with all his other possessions, to the same friend, and they had passed to his widow when the friend died in 2021.

The woman, who had been unaware that she owned Hilton’s estate, donated the rights to Chadwick on the condition that he must do his utmost to breathe life back into his work.