In recent years, Mexico has become one of the most complex environments for writing and publishing, where literature intertwines with survival. In a country plagued by rising violence and organized crime, the publishing industry has evolved into more than just a space for creativity, it has become a tool of resistance and cultural resilience. Books tackling themes of violence, corruption, and identity are increasingly prevalent, while demand grows for works of nonfiction and survivor testimonies, in an effort to understand the reality and confront it with the written word before resorting to arms.

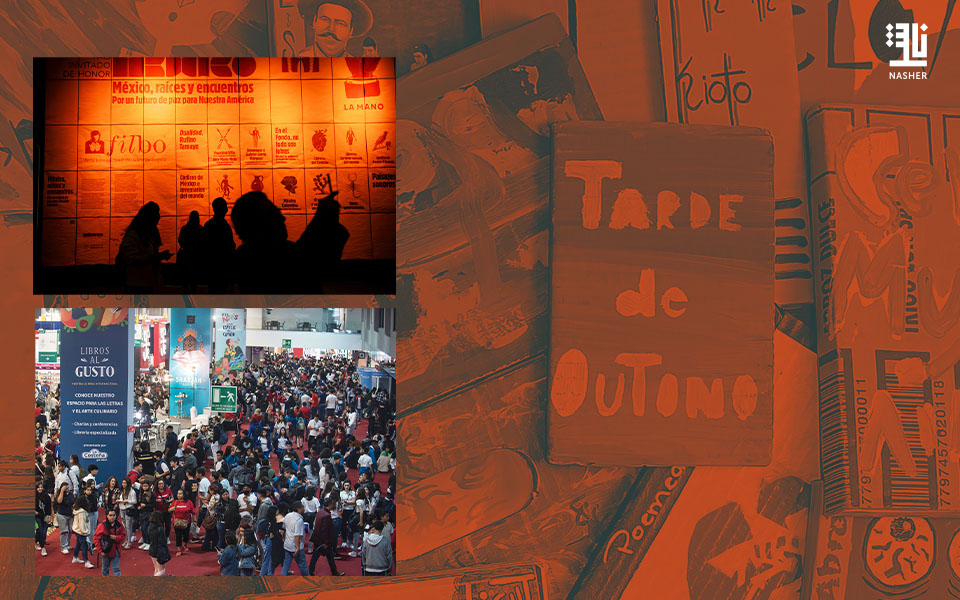

Despite the challenging climate, Mexico has witnessed remarkable growth in independent publishing houses, which position themselves as ethical and creative alternatives to major publishers. These presses focus on marginalized voices, championing themes such as social justice, women’s rights, and the memory of victims. Among the leading names are Editorial Sura, Alfaguara, and Sexto Piso, which have become platforms for bold and compelling writing. At the same time, they strive to survive in the market by innovating distribution methods and reaching readers, particularly through book fairs and cultural events.

Young Mexican authors are gaining increasing visibility on the global literary scene, especially those writing in Spanish while living abroad, such as Valeria Luiselli and Javier Cercas. However, this international presence does not mask the local challenges: reading rates remain low compared to other Latin American countries, and access to books is hindered by economic and geographical barriers. In response, civic initiatives such as “Everyone Writes” and “People’s Libraries” are working to spread reading culture among underserved communities.

Interestingly, the shift toward digital publishing in Mexico is progressing slowly. Most books are still consumed in print, despite the availability of some digital editions. Apps like Bookmate are beginning to gain traction among younger readers, alongside government efforts to digitize public library content. Still, the greatest trust lies in direct, human interaction between writers and audiences, through literary gatherings, salons, and festivals.

In Mexico, despite all the circumstances and challenges, books are not seen as a cultural luxury but as a tool for understanding the self and society, and for rewriting reality in a more humane language. Amid noise and fear, books remain a window to hope, a way to safeguard memory from oblivion and protect the truth from disappearing.