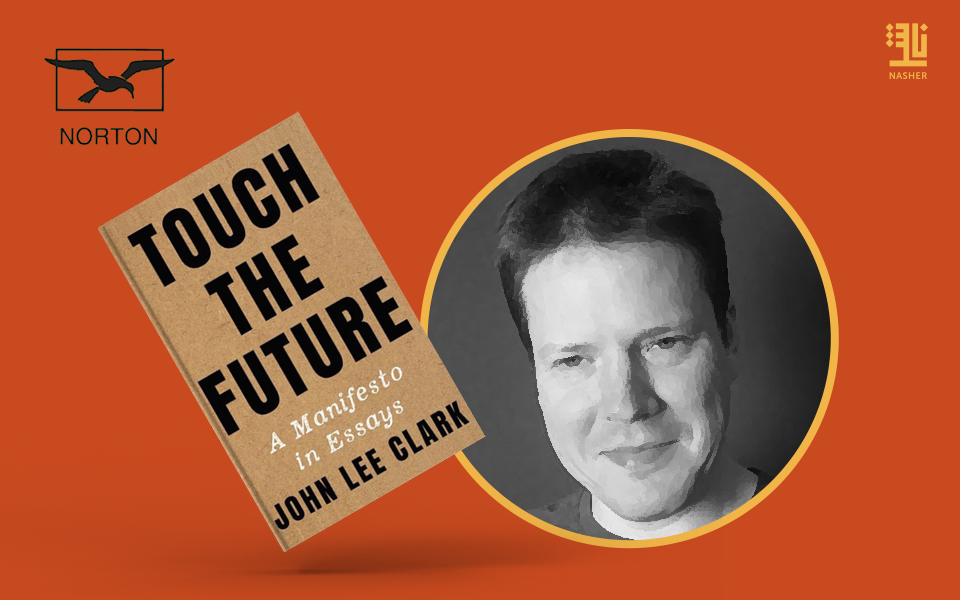

A fascinating window into another world of communication is coming from US publisher Norton in October. Touch the Future: a Manifesto in Essays is by Deafblind poet, essayist, and educator John Lee Clark. In it, he tells the story of how the language that would come to be called Protactile was first developed in Seattle in 2007 and discusses his hopes for this new languages future.

In Protactile, communication takes place by touch and movement focused primarily on the hands, wrist, elbow, arm, upper back, and when in a seated position, knees and the top of the thigh. In formal instruction of Protactile, while sitting and facing a conversation partner, the “listening hand” has the thumb, index finger, and little finger extended, and is rested on the thigh of the other participant. So for example, several rapid taps on the thigh with all four fingers would indicate “yes,” whereas a rapid back-and-forth brushing movement with the fingers would indicate “no.”

In the essay Always Be Connected, Clark traces the movements origins to a 2007 shortage of sighted ASL [American Sign Language] interpreters in Seattle that prompted DeafBlind community leaders to hold meetings without them, organically producing new means of communication. Norton says: Clark notes that ASL posed difficulties for DeafBlind people, who would listen by placing their hands over a speakers hands as they signed despite only 30% of ASL being decipherable by touch. So when the Seattle DeafBlind community decided to forge ahead without interpreters, they developed an ASL offshoot, called Protactile, that uses intricate systems of touch to communicate.

Looking ahead, the author says: It may seem strange to say, but I hope that, on one level, my book will quickly grow to be outdated. This will be because what the movement has suggested or only just begun to make manifest has come to pass.