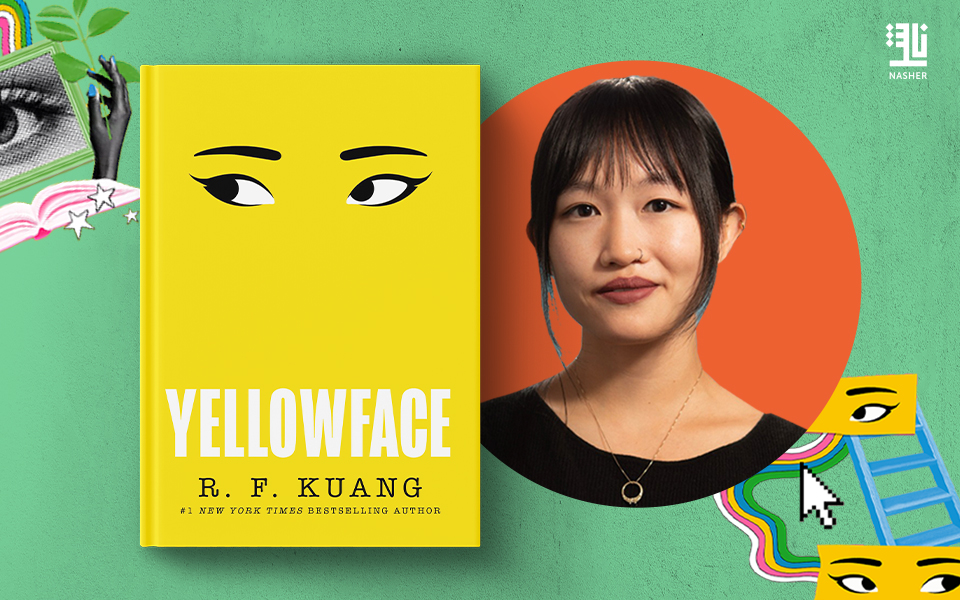

Yellowface is set in the world of publishing that tells the tale of two young novelists in Washington DC. June Hayward is a novelist whose coming-of-age debut was released to middling acclaim. Wracked by careerist envy, June is debilitated by the success of her friend and fellow writer Athena Liu, the newly-crowned Asian American darling of the literary world. Athena, at the ripe age of 27, has three bestselling novels, a Netflix deal, and “a history of awards nominations longer than [a] grocery list,” while June is adrift with an agent who doesn’t seem to even like her work. Knowledge of Athena’s success only exacerbates June’s writer’s block. She was “derailed for days” after hearing of her friend’s six-figure option deal. The novel starts with the pair toasting Athena’s success in her ritzy apartment after a night on the town; Juniper, our narrator, is choking down her resentment when, suddenly, Athena is literally – and fatally – choking on a homemade pancake.

After the blur of 911 calls and blue lights, a shellshocked June gets an Uber home and starts the motions of public social media mourning, guiltily aware that she had never really liked Athena that much anyway. But stuffed in her bag is the completed manuscript for Athena’s new novel about Chinese labourers in World War I. It’s type-written. No back-ups. No electronic trail. It’s the perfect literary crime. June quietly takes it and redrafts it as her own work. It is published to great acclaim. June finally has the literary success which she has craved for so long.

But right from the very start, there are cracks. Eyebrows are raised at this novel about Chinese labourers being authored by a white woman. June’s publishers encourage her to rebrand as Juniper Song, using the middle name given to her by her hippy mother. Author photographs are taken which are carefully lit to suggest racial ambiguity and an author bio is drafted to emphasise the same.

She manipulates Athena’s mother to keep her from sharing her dead daughter’s research notebooks to a university archive, fearing they contained evidence of her plagiarism. Juniper still basks in the glow of success – at least until Twitter raises its collective eyebrow and she’s mired in an ever-widening plagiarism scandal. She extorts Athena’s ex-boyfriend and gets an editorial assistant who harboured suspicions about her writing fired.

We learn that her plagiarism is motivated by puerile revenge, a tit-for-tat since Athena, so June claims, stole from her first. June was sexually assaulted in college, an experience that’s callously recounted in a few pages over the novel’s halfway mark. The assault is alluded to only once beyond that section. June claimed to bury her trauma “so deep in the back of my mind that [it] wouldn’t resurface until therapy sessions many years later.” We learn that June first disclosed this sexual trauma to Athena, who, mined it for a short story.

As the excuses pile up, Kuang convincingly keeps the ground shifting as to whether Juniper’s confession is just another con trick, as well as concealing the scale of her misdemeanours. As a tale of rivalrous friendship that morphs into lurid revenge melodrama and even a sort-of ghost story, Yellowface keeps us agog, narrowing its eyes all the while at an industry’s attitudes towards racial diversity. Still, it’s a thriller about the book trade – the appeal is niche – and you can sense Kuang’s uncertainty about what does and doesn’t need explaining. The reader who cares to know that the central characters became fast friends over a shared love of Elif Batuman’s The Idiot (“‘It is the perfect campus tale,’ Athena said, articulating clearly every feeling I’d ever had about the novel”) isn’t, I suspect, a reader who needs to be told that paperbacks are cheaper than hardbacks, as Juniper at one point handily lets us know.

Yellowface does acknowledge that books and authors are manufactured commodities that can be launched to bestseller status with the help of a marketing team. There is a lot a writer can gain from commodifying their identity, in abiding by the unspoken rules and rituals of a cutthroat industry. It’s “publishing [that] picks a winner,” June says, “someone attractive enough, someone cool and young and, oh, we’re all thinking it, let’s just say it, ‘diverse’ enough—and lavishes all its money and resources on them.” The characters seem to shrug their shoulders at the system’s arbitrary selection with little care for its effect on literature and prose. In Yellowface’s world, there are no writers worth mentioning beyond publishing’s institutional purview. You’re either “chosen” or you’re not—and even the chosen writers, like Athena, are treated somewhat poorly because the industry is dominated by affluent and subliminally racist white people

As the novel progresses, these narrative cliffhangers serve as fleeting proof of June’s entitled delusion. “It’s the internet that’s f*****, not me. It’s this contingent of social justice warriors, these clout-chasing white ‘allies,’ and Asian activists seeking attention who are acting up. I am not the bad guy. I am the victim here.”

Yellowface is a fast paced and an intriguing tale of a crime committed in the name of justice in a filed that is far from the morality and principles that are often associated with it. Despite the narrative portraying June as the ‘villain’ we the reader can’t help feeling some kind of sympathy with her and at some point even rooting for her not to be outed. We have given it 8/10.

Yellowface by Rebecca F Kuang is Published by HarperCollins UK