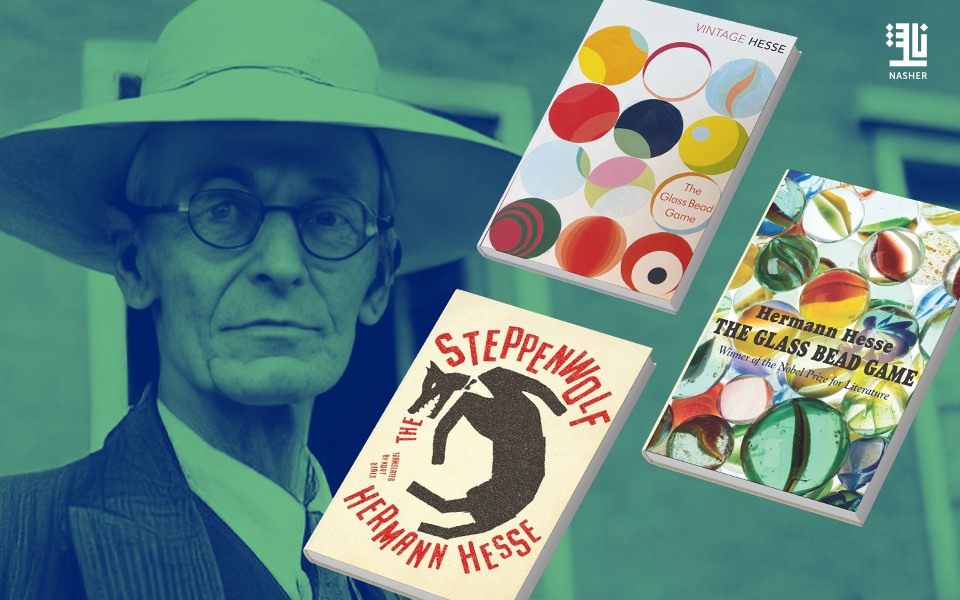

On July 2, we mark the birth anniversary of the great German writer Hermann Hesse (1877–1962), one of the most influential literary voices of the 20th century and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1946. Hesse was renowned for works that delve into the human and spiritual depths, prompting readers to question their existence and unravel their relationship with the world. He was not merely a novelist, but a seeker of meaning who wrote in a contemplative style that turned each of his novels into a personal journey inward rather than outward. While his contemporaries were preoccupied with the noise of modernity and war, Hesse chose solitude and listening, making writing a tool for inner purification.

Hesse was born in the small town of Calw in southern Germany to a father working in publishing. His early life was marked by psychological struggles, and as a teenager, he even attempted suicide and was admitted to a mental institution. That experience proved to be a turning point; his pain transformed into awareness, and he realized that salvation could not come from the outside, it had to be found within. Writing became his way of resisting collapse. His works, therefore, are more than mere stories; they are human experiences written in symbolic, philosophical language.

In his acclaimed novel Steppenwolf, we encounter Hesse at his most somber and honest. The novel explores the internal divide between the “civilized” human and the primal being. It pulses with tension between the desire to belong to society and the fear of being consumed by it, between refinement and savagery, intellect and indulgence. Hesse wrote the novel during a midlife crisis, and it became a confrontation with himself. He later said, “Anyone who has never felt himself to be a lone wolf will never understand this book.” Steppenwolf is more a mirror of internal alienation than a critique of society.

In The Glass Bead Game, arguably his most complex and mature work, Hesse offers a sweeping philosophical vision about knowledge, elitism, and the fate of culture in a rapidly changing world. Set in an imagined society obsessed with science and art, the intellectual elite play a sophisticated “game” combining philosophy, mathematics, and music, yet it drifts ever further from real life. Through this, Hesse warns against the intellectual’s detachment from reality and raises profound questions about the value of purity in thought when disconnected from human suffering.

Hesse’s personal life deeply influenced his literature. He endured failed marriages, lost a son, and lived in self-imposed isolation in Switzerland during both World Wars. He disliked public life but was far from neutral; he wrote against nationalism and militarism, and advocated for both personal and collective peace. Although he refused to align with any party or ideology, his voice remained a moral compass in literature, searching for the human amidst brutality and fragmentation, reminding us that true reform begins within.

In 1946, the Swedish Academy awarded Hesse the Nobel Prize in Literature in recognition of “his inspired writings which, while growing in boldness and penetration, exemplify the classical humanitarian ideals.” The award was a belated acknowledgment for a writer who chose solitude over fame. By then, he had already become a literary icon in Europe, attracting loyal readers in the post-war generation and, later, among the youth movements of the 1960s and 1970s, who saw him as a writer of freedom and inner awakening.

In an age of accelerating pace and fading meaning amid technological noise, Hesse’s works endure as a reminder that one need only listen to the inner voice, acknowledge one’s fragility, and the path will reveal itself. On his birth anniversary, we return to Hermann Hesse not only to read him, but to recover the courage to be honest with ourselves – and, in our own ways, to write our journey toward meaning.