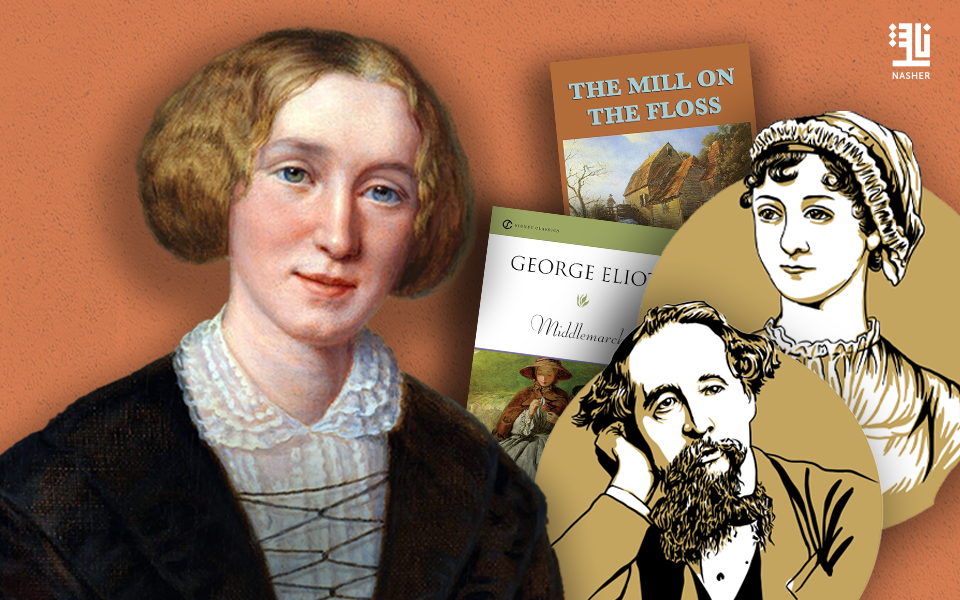

In the history of English literature, names such as Charles Dickens and Jane Austen shine as towering landmarks of the classic novel, while the name George Eliot – or Mary Ann Evans – often stands in the shadows, despite her being one of the most influential authors of the nineteenth century. Eliot chose a masculine pen name to avoid the prejudices faced by women writers in her time, yet she later paid the price for that choice, as her presence in literary memory remained far less prominent than her achievements deserved.

Her novels, including Middlemarch and The Mill on the Floss, delve deep into the human psyche and redraw the intricate details of social and political life with unprecedented realism. Her style was distinguished by a fusion of narrative storytelling with philosophical and moral inquiry, lending her works an added layer of intellectual depth. Yet this very intellectualism often made her less accessible to the wider reading public, which was more drawn to the direct drama and heightened emotion of Dickens’s works, or to the quiet romance found in Austen’s novels.

Social and critical circumstances also played a part in marginalizing her place in the canon. Her works were repeatedly placed in comparison with those of her male contemporaries, and judged by critical standards steeped in masculine ideals that equated “universality” and “the general human experience” with male perspectives. Meanwhile, women writers, even the most accomplished among them, were confined to the narrow label of “women’s literature,” a category that curtailed their reception as voices capable of transcending gendered boundaries.

Beyond the shadows of Dickens and Austen, Eliot’s career reveals her profound influence on the evolution of the realist novel. She inspired later authors – from Virginia Woolf, who called her “the greatest English novelist,” to a generation of writers who embraced her deep insight into human character and its psychological construction, a vision ahead of its time that opened new horizons for the modern novel. Her books do more than tell stories; they reshape the reader’s understanding of human relationships, raising questions about morality, individual freedom, and the meaning of life in a changing society.

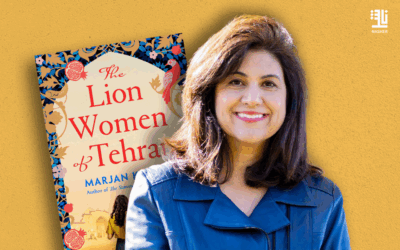

It can be said that rediscovering George Eliot today is not merely an act of critical correction, but an invitation to revisit the classics with fresh criteria that recognize the worth of voices that resisted marginalization. Perhaps the time has come to place her alongside Dickens and Austen, not as “the female face” of Victorian literature, but as one of its central pillars, a writer whose mark is no less significant than that of any of her contemporaries, not only in England but across the world.