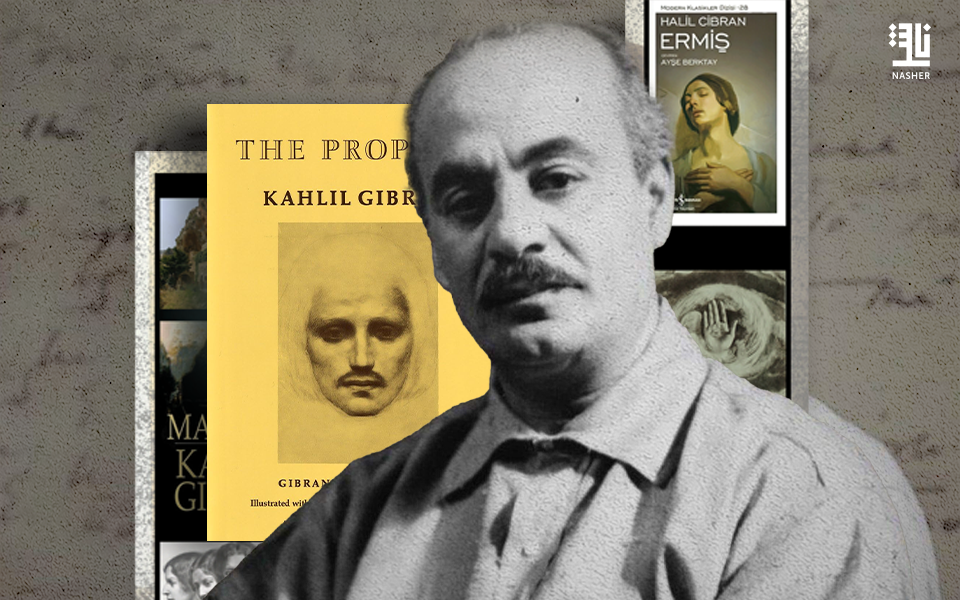

On his birth anniversary on January 6, the name of Gibran Khalil Gibran returns to the cultural spotlight, not as a writer encountered through a complete reading experience, but as a renewed presence within the digital sphere. He is widely visible today, yet in a form markedly different from how twentieth-century readers knew him. Gibran is no longer summoned through books alone, but through short phrases, images, and swiftly circulating quotations across platforms. This shift raises a legitimate question: does Gibran still speak as a contemporary writer, or does he survive in collective memory through linguistic fragments detached from their original texts?

On social media platforms, Gibran appears almost as though he were written for the age of rapid quotation. His condensed language, meditative tone, and ability to distill wisdom into a single sentence have made his words ideally suited to digital circulation. Yet this wide reach does not necessarily translate into genuine engagement with his work. Many encounters Gibran for the first time through an image bearing his name, without any awareness of the intellectual or narrative context from which the line emerged, transforming the text from a literary experience into a visually shareable object.

Here, the issue of extracting texts from their contexts becomes especially pronounced, an issue not unique to Gibran, but particularly acute in his case. When his sentences are severed from their larger structures, they sometimes lose their internal tension or philosophical depth, becoming generalized aphorisms open to any interpretation. This selective use reshapes Gibran’s image in the minds of new readers, reducing his expansive literary project to a single dimension, often spiritual or emotional, at the expense of its intellectual and human complexity.

Yet this transformation cannot be dismissed as decline alone. Social media, for all its reductiveness, has brought Gibran back into the orbit of generations who might never have encountered him through the printed page. Many young readers arrive at his complete works after a single quotation sparks their curiosity, making digital platforms a point of entry rather than a final destination. The question thus shifts from condemning the phenomenon to understanding it: how can cultural publishing engage with this presence without hollowing it of meaning?

Ultimately, Gibran today appears as a writer suspended between two eras: the age of the book and the age of the screen. He is neither confined to quotations alone nor fully present as a deeply read text, but exists in an in-between space that reflects our changing relationship with literature itself. On the anniversary of his birth, the more pressing question is not whether Gibran remains contemporary, but whether we are capable of reading him anew, reading that honors the spirit of the text, understands the conditions of the present, and reconnects literature as lived experience with reading as a vital human act.