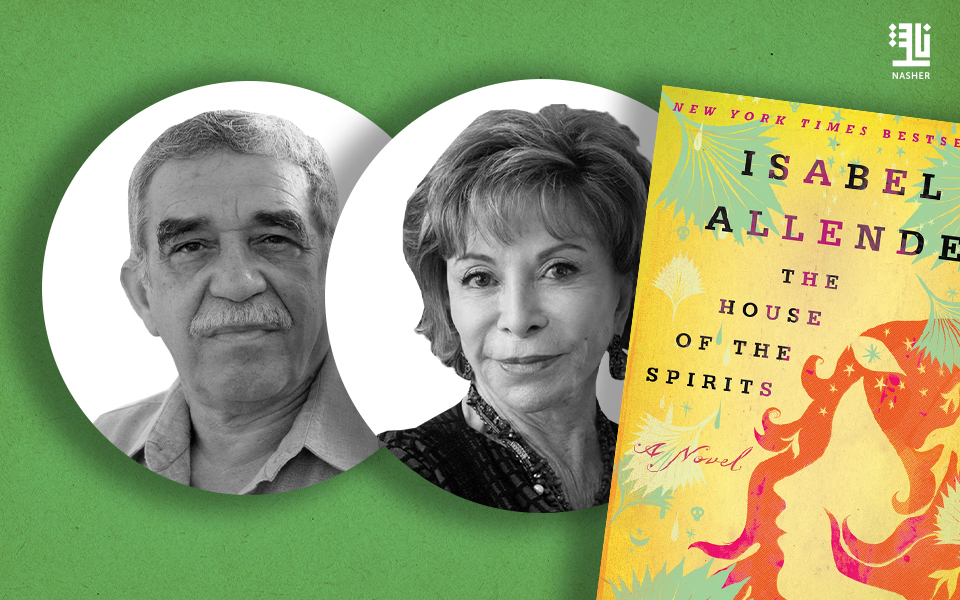

Gabriel García Márquez was not merely a Colombian visionary who penned beautiful fiction, his work marked a turning point in world literature. He transformed magical realism from a regional phenomenon into a global literary current. As his influence reached its height in the 1980s, Isabel Allende emerged as a parallel voice, one that echoed the same themes of magic, memory, realism, and family, yet refracted them through a distinctly feminine and Chilean lens. What united the two wasn’t only a shared aesthetic, but a deep belief that storytelling could reveal truths unreachable by politics or history alone. And so, decades after Márquez’s towering presence, one wonders: Has Allende managed to sustain the spirit of magical realism? And does that spirit still resonate in today’s literary world?

When Allende published her debut novel The House of the Spirits in 1982, the same year Márquez received the Nobel Prize, many assumed she was following in his footsteps. But it soon became clear that her work was not a replication of an emerging genre, but rather a reimagining of it from within, reshaped through a woman’s voice and vision. In her fiction, the miraculous doesn’t spring solely from mythology, but from wounded memory, familial silence, and the subtle strata of history that official narratives tend to obscure. It’s a perspective that has resonated with readers far beyond South America.

Allende approaches magical realism as a tool to articulate the unspoken, particularly in the context of Latin America, a region scarred by coups, repression, and enforced forgetting. In novels like Daughter of Fortune and Portrait in Sepia, magic does not stand apart from history, it reflects it in blurred outlines or offers a path beyond it, psychologically and emotionally. What makes her storytelling remarkable is how she renders the extraordinary as ordinary, how wonder is embedded in daily life, in the structures of feeling, family, and community.

As global literary tastes shift, with the rise of gritty realism, speculative fiction, and postmodern experimentation, magical realism has gradually receded from the center stage to a more reflective margin. Its marvels no longer astonish in the same way, and perhaps readers no longer rely on them to interpret a complex world. Even Allende herself, in recent works like Violeta, leans more toward historical narrative and memoir, as if quietly acknowledging that the magic has played its part, and now it’s time to remember.

Yet Allende’s literary significance is not measured solely by her use of magical realism. Her lasting relevance stems from her voice as a global female author who continues to evolve. Magical realism was never her destination, it was her entry point. And now, she moves gracefully through other forms of storytelling that carry equal weight. Her readers seek not just enchantment, but depth, those tender, human moments that transform the mundane into something transcendent.

Perhaps the real question is not whether magical realism has faded, but whether our need for it has. In an age dominated by immediacy, screens, and stark realities, magical realism may appear to some as a stylistic luxury, at least in literature. Yet when written with sincerity, it still reminds us that life cannot be reduced to what we see, and that memory, longing, love, and loss remain gateways to the magical. In this sense, Isabel Allende, long after Márquez, remains a testament to fiction’s quiet power to whisper where reality falls silent.