For centuries, Brazilian literature was shaped by a male-dominated vision, reflected both in its narratives and its structures. Yet Brazilian women never stopped writing, even when pushed to the margins. Many wrote in the shadows, under pseudonyms or behind troubled social facades. But since the latter half of the twentieth century, Brazilian women writers have steadily reclaimed their place, not merely as dissenting or parallel voices, but as central figures in telling the national story, with all its existential, social, and intimate complexities.

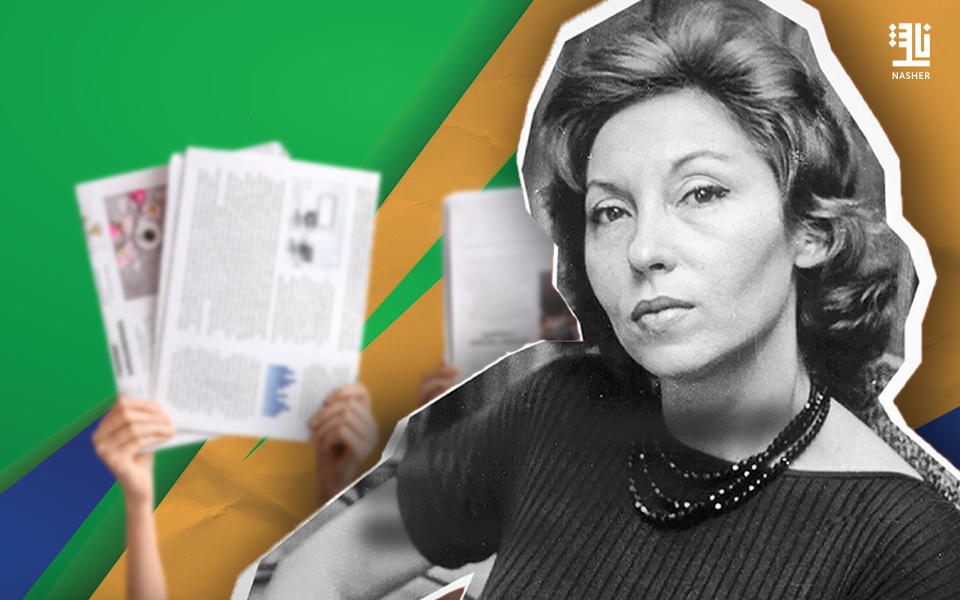

Among the icons of this shift is Clarice Lispector, whose work marked a radical turning point in Brazilian literature. She wasn’t simply a woman who wrote, she wrote in ways no one had before, with a language that was sharp, disorienting, and defiantly unconventional. Alongside her, other women writers emerged, carrying with them the weight of social, feminist, and racial struggles. Among them is Conceição Evaristo, whose writing fuses poetry with narrative and politics with memory, drawing on Afro-Brazilian roots to become one of the country’s most resonant literary voices today.

In parallel with this creative maturity came the rise of feminist publishers who established independent presses dedicated to women’s literature, reshaping the cultural power structure of publishing. Among the pioneers was Editora Mulheres (“Women’s Publishing House”), founded in 1995 in Florianópolis by three retired university professors. The initiative gave a platform to female writers from remote regions and marginalized ethnic backgrounds, far from the market’s demands and fast-selling trends. The publisher was no longer just a technical intermediary, but an active cultural force guiding what gets published and for whom.

This transformation coincided with a notable rise in literary awards granted to women, and a growing number of female authors being translated into other languages. Yet the path was anything but smooth. Many women writers still face structural challenges, marketing hurdles, critical bias, and systemic exclusion within traditional publishing houses. Here, independent prizes and feminist literary events play a vital role in granting recognition and visibility to these voices.

Today, women’s publishing in Brazil is no longer a fringe movement or passing wave, it is an established practice that redefines the relationship between literature and identity. When women write, they do more than tell untold stories; they expand the very boundaries of language, theme, and form. Through feminist presses, grassroots initiatives, and shifting reader sensibilities, Brazilian women writers are no longer waiting for recognition, they are claiming it, and reshaping the literary landscape of Latin America in the process.