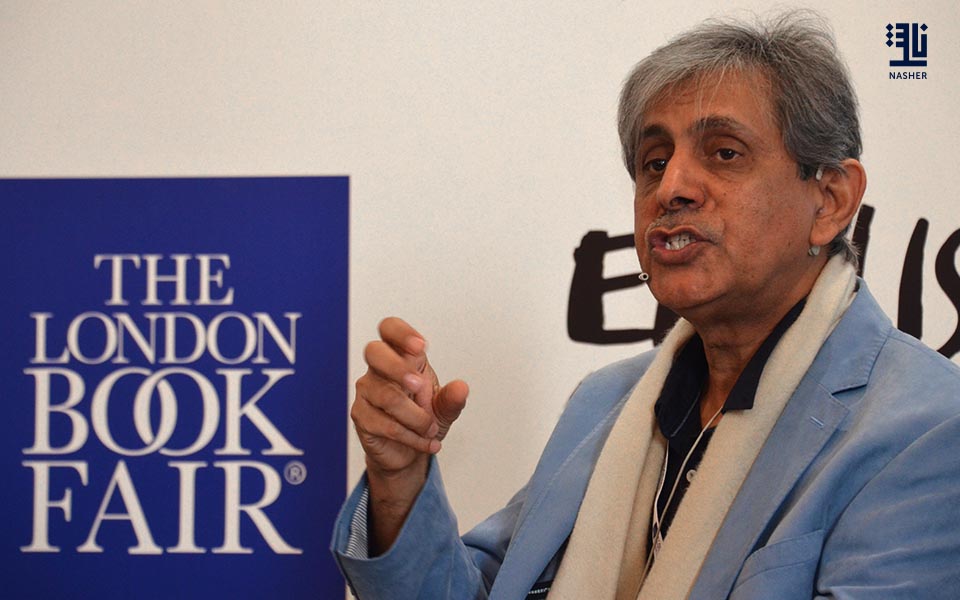

Poetry has played – and still plays – an important role in preserving Emirati and Arab heritage, the celebrated Emirati poet Khaled Albudoor told delegates in a fascinating in conversation session with Erica Hesketh of the Poetry Translation Centre.

The session was sponsored by English PEN, the British Council and the Sharjah Book Authority, whose chairman Ahmed Al Ameri was in the audience.

He spoke evocatively about his childhood in a village near Dubai in the Sixties, painting word pictures of an idyllic upbraning. “We would play in the sea and on the dunes of the desert. At home my mother loved poetry and I came to it because of cassettes of singing that we had. I started to write poetry to impress my mother.

“In every family, even if there wasn’t a poet there was a love of poetry. Poetry was the main source of heritage. In the Nabati tradition the poet carries the history of the tribe and of his family.”

He recalled playground competitions at school “when I would write some lines and then someone else would come along with more lines and say ‘but can you do it like this?’ It was a sort of challenge”.

He said that at high school he mainly wrote verse in the classical, Arabic tradition – the world of Mutanabi and other greats – where the themes were about the past. “It was later that I began to look at myself and my place in the world, and poets started to explore where they found themselves in the world. We started to say things in our own way, to experiment with language.”

He interspersed his reflections with poems read in Arabic and English, one touchingly concluding ‘everything is there but you’ and another saying ‘time to remember and time to forget’. As he read his arm flowed and waved like a palm frond.

He said he was fascinated by language, about choosing the right words and their symbolic power, and he said that completing a poem can take months as he keeps returning to it.

Although he said the novel was now a powerful force in the Gulf, he said a love of poetry still existed. “It’s still there, through readings, festivals, book fairs – and now through social media, on Instagram.” He recently posted a video of him reading a poem on Instagram which clocked up 10,000 views in an hour. “We could never get this exposure in the past.”

Interestingly, because the movement away from classical Arabic poetry has been widespread, people are now reacting against that too. Hesketh observed: “People always react against what went before, so now there is a move away from modern poetry.”

Albudoor agreed to a point. “Yes, people can sometimes feel alienated from their own heritage because of new media and the modern world, and so they feel a return to those old voices.”

The irony of course, is that they will then use new media – their smartphone – to upload a classical style poem.