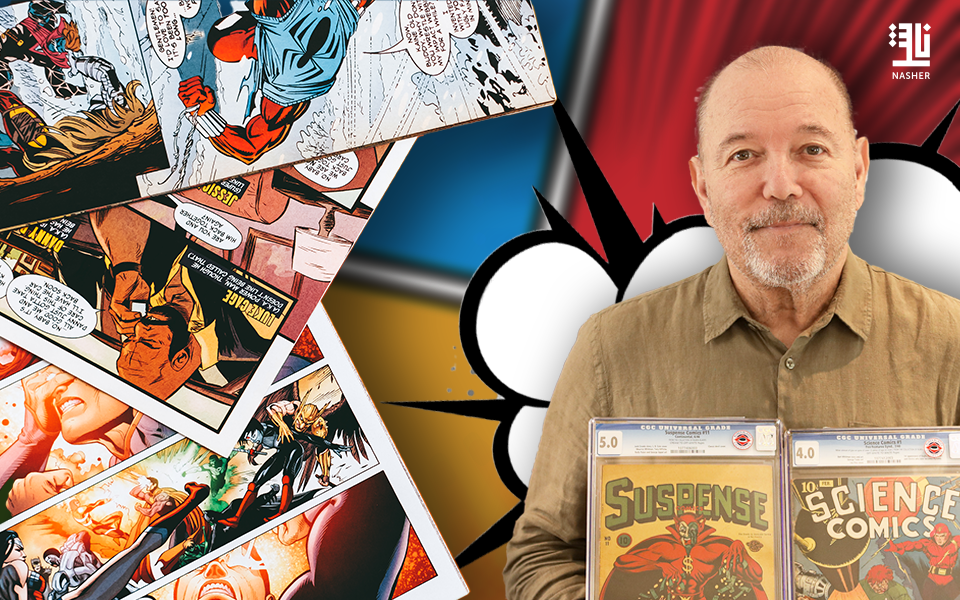

Collecting comic books has become one of the fastest-growing hobbies in the United States and beyond, with thousands of specialized bookstores and dozens of annual conventions bringing together collectors, traders, and investors. Over time, comics have evolved from being a medium of entertainment and casual reading into a thriving market that breaks records at international auctions, where rare issues sell for staggering amounts, turning these colorful pages into part of a cultural and economic industry in its own right.

The major turning point came with the rise of grading companies that established precise standards for evaluating condition and quality. The most prominent of these is CGC (Certified Guaranty Company), founded in 2000, which has since graded millions of comic books, trading cards, and posters. Grading instantly elevated the value of comics, moving their assessment beyond emotion or guesswork to a clear scale ranging from 0.5, denoting a heavily damaged issue, to 10.0, reserved for flawless copies in pristine condition.

What might seem like a technical detail has, in fact, become a strict economic benchmark. Auction houses now prioritize graded issues, since grading provides buyers and investors with a transparent price index and ensures greater confidence in transactions. As a result, values have soared within just a few years. A striking example is Detective Comics No. 27 (1939), which introduced Batman. A copy graded 5.0 sold for $482,000 in 2018, then leapt to $1.125 million in 2021, nearly tripling its price in less than three years.

The all-time record, however, belongs to Superman No. 1 from the same year. In April 2022, a copy graded 8.0 sold for $5.3 million, reflecting not only the mythic status of the character but also the extreme rarity of high-grade surviving issues. These sales illustrate how a comic book, once bought for mere cents, can become an asset rivaling fine art or antiquities, especially when it captures the moment of birth for an iconic superhero.

Grading has also introduced a visual culture of its own through the colors of the holders used to encase comics. Blue denotes standard editions, yellow indicates signed copies, green signals missing elements, and purple marks restored issues. While simple at first glance, these colors carry precise meanings that can dramatically influence a comic’s market fate, symbols in a coded language understood only by seasoned collectors.

Comic book enthusiasts themselves fall into distinct schools. Some chase only first issues; others pursue the first appearances of major characters. Many aim to build complete runs of series such as Batman or Spider-Man, while others cherish classics like Mickey Mouse, The Smurfs, or Scooby-Doo. A growing group approaches collecting as pure investment, treating each issue as a financial asset whose value may rise over time, not unlike currencies or works of art.

What sets the world of comics apart is its ability to open doors on multiple levels: the joy of reading that shapes childhood and adolescence, the nostalgia that drives new generations to hunt for fragments of a shared past, and the economic dimension that has transformed the hobby into a global market with its own institutions and auctions. In the end, these colorful pages bridge imagination and commerce, linking the innocence of childhood dreams with the calculations of adulthood.